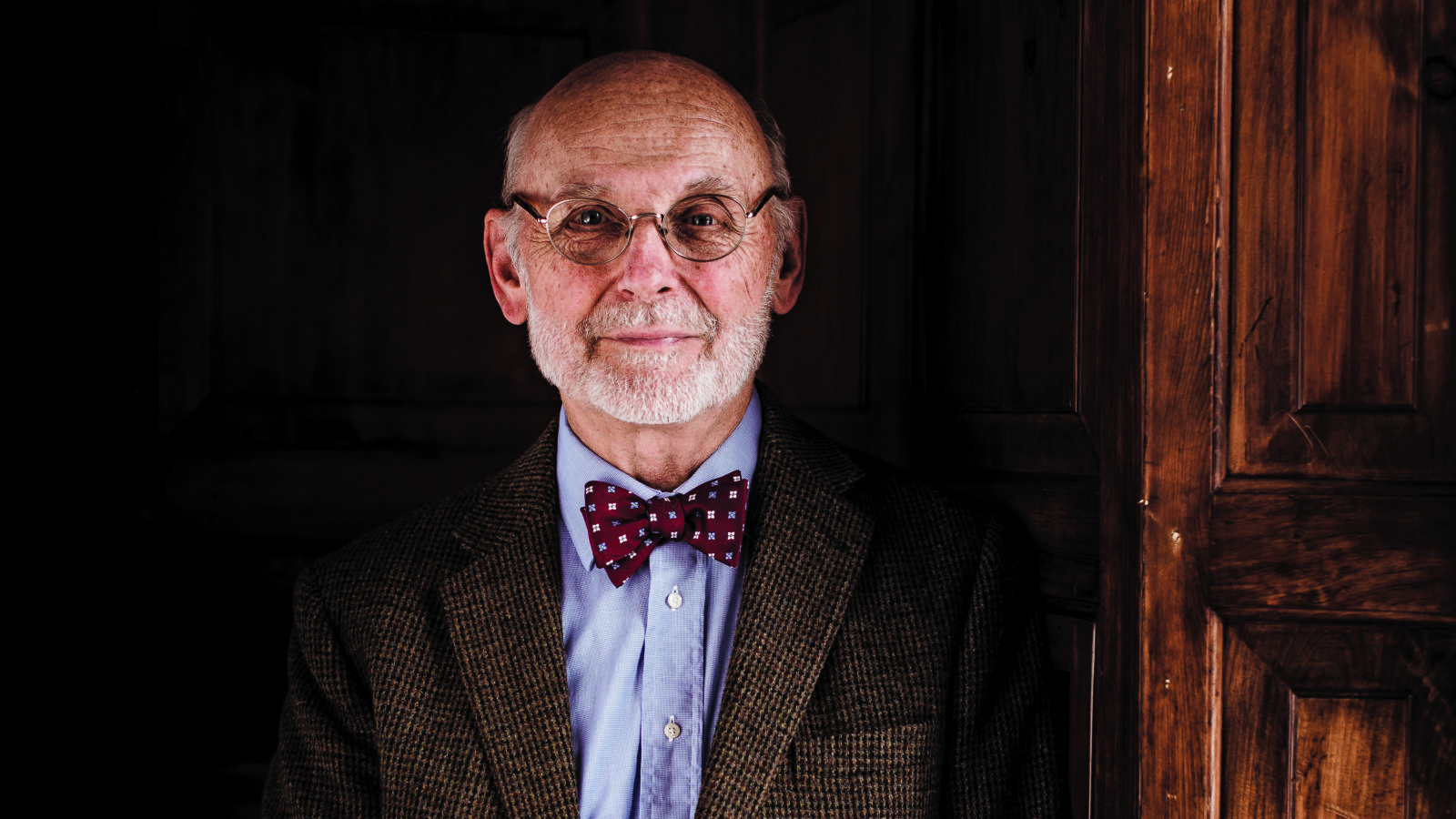

Maritime detective David Hebb ’61 has made a career of finding legendary shipwrecks. Historian by training and adventurer by nature, he loves the intellectual challenges posed by his work. The treasure is just a side benefit.

Research historian David Hebb ’61 is very good at finding things. Specifically, he is good at finding treasure. Gold bullion, pieces of eight, sea chests overflowing with silver, artifacts of historic or artistic value. In the rarefied world of ocean salvage, deep-pocketed investors—banks, marine exploration firms, high net-worth individuals looking for a hit of adrenaline with their returns—turn to Hebb to locate and identify historic shipwrecks. He is the mild-mannered scholar whose careful investigations lie behind breathless headlines—“Divers Recover Billions in Treasure from South American Wreck!” For Hebb, who with his wife, Columbia University professor Jane Waldfogel, divides his time between homes in New York and London, the quest typically begins amid the stacks of Europe’s great libraries and archives. Poring over endless pages of feathery script, he hunts through ancient documents for clues to unravel the mystery of a sunken galleon. “There is a great pleasure or sense of fulfilment in finding and recovering something that has been lost for hundreds of years and bringing it back into the world,” he says. We caught up with him between voyages to learn more about his fascinating work.

So, David, how does one become a seeker of lost ships?

In my case there were childhood influences. Growing up in Pittsfield, one of my friends lived in Herman Melville’s old house, Arrowhead, and we often talked about Moby Dick and seafaring. I spent much time playing in the Housatonic River, building rafts and daydreaming about going to sea. Also as a boy, I loved listening to a long-playing record my family had of radio broadcasts by the newsman Edward R. Morrow. It was called “I Can Hear It Now” and I remember he talked about the founding of the United Nations and how Edward Stettinius, the U.S. Secretary of State, had “seen more of the world than Marco Polo.” And I thought, “Well, everyone should see more of the world than Marco Polo. This is the 20th century!” Thirdly, I think my outlook was influenced by being adopted, growing up in a family not of my birth parents. In a way, because of this I felt I had a freedom to do something different. I didn’t feel some inherent need to conform to family traditions. There was a world out there, and seeing it meant taking chances.

What was the biggest chance you took?

I went into the army during the Vietnam War. At Williston, if I was known for anything—known for anything good, I should say—it was for winning every year a Time magazine current events contest in which the school participated. I followed current events closely, and I felt strongly that if we were going to be involved in Vietnam, I should serve. The headmaster used to say we were privileged and with privilege came responsibility. I thought our involvement was certainly wrong, but I had imbibed this notion of obligation. So I took ROTC in college and went into the army after graduating from Washington and Jefferson College in 1965. Oddly, ironically, wartime service had a liberating effect. I didn’t see combat, spent most of my time in South Korea. The North Koreans were attempting to start a guerrilla war and there was a lot of border shooting. I didn’t live in fear, but there was a sense that you were at risk. Of my immediate circle in college, about 10 in number, one was killed, a Marine helicopter pilot, two others were wounded, and a third was drenched with Agent Orange and suffered health problems and an early death as a result. I think this wartime experience, though I suffered nothing directly, made me feel that anything that followed couldn’t be so bad. So what if you tried something and it didn’t work or you failed. There were far worse things in life.

When did you decide to study history?

The head of history during my time at Williston was Archibald Lancelot Hepworth. Quite a stern and demanding teacher, but he saw that I had ability, a mind suited for historical study. His recognition was important to me. He encouraged me and gave me the sense that I was good at something. When I got out of the army, I started law school. I remember looking up from briefing cases for class one day and seeing an upperclassman, second or third year student, bent over a massive tome. The Law of Commercial Paper. I thought, I don’t want to do that. The next day I applied to graduate school in history. I got a master’s from American University and then decided to go to England for my Ph.D.

Why England?

I’d had a course at Williston in English history, and then when I was doing my master’s, one of my interests was the English Civil War. It struck me as being quite similar to what we were going through in the late 1960s in the United States, with society almost coming apart at the seams. The other part, going back to Marco Polo, was seeing more of the world. I’d been in Asia a bit now, so why not Europe? Why not study there? I had met two visiting professors from England at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, so I wrote to them and said, “I’d like to come over to study.” One of them was Conrad Russell, Lord Russell as he became, who was in London. I told him what I was thinking of doing and he said it sounded interesting, would I like to study under him? So I did that. He was very much a research historian. He had an appreciation for archival research. That appealed to me and still does. Now if I get a free day, I go to the archive and look at documents. It’s like Christmas for a small boy, all these packages. I eventually finished my dissertation and began teaching at the University of Essex.

When did shipwrecks come into it?

During this period when I was doing my Ph.D., the Institute of Historical Research in London would put on seminars in a range of subjects. I used to work in the archive during the day, then go to seminars in the evening. The Renaissance Italian seminar was run by Sir John Hale, the distinguished historian, and it was through him that I got involved in shipwrecks and treasure hunting. One of his friends from student days at Cambridge had gone into the City of London, the Wall Street of Britain, and made a lot of money. He’d then set up a North Sea oil services company. This involved divers—and all divers are interested in shipwrecks! They decided they wanted to recover the fabled pay ship of the Spanish Armada, but before they put money into it, they needed to find out if the wreck they had in mind off Scotland was indeed the pay ship. Sir John knew that I had worked in the Spanish archives for my thesis. He said to me, “Would you like a job?” It was summertime, I could use a bit of money. Some of the research involved going to Scotland. I thought, “I can spend my days in the archive in Edinburgh and go to the arts festival in the evening. And someone will pay me to do this!”

Was it the right ship?

I determined the wreck was not the legendary pay ship of the Armada. It was a just a merchant vessel. But in my presentation to the investors, I had enough wit to add at the very end, “If you are interested in finding something of value, I suggest that you look at other areas of the world and other trades.” They liked that idea. For the next few years, I spent my holidays from teaching doing research on lost ships. At some point they asked if I would take it on full time. And I thought, “Well, I can always go back to teaching, but no one is ever going to come along again and ask me to find treasure.”

What’s the most exciting part of your work?

For me it’s the puzzle-solving. That’s what motivates me. You start with one line of investigation, maybe it works out, but quite often it doesn’t. You back up and ask, “Where do I go from here?” For example, one of my jobs involved a 17th-century Spanish ship called the Concepción. It was part of the Manila galleon trade, carrying precious metals from Mexico across the Pacific to the Philippines, where they’d trade for valuable commodities from Asia. The Concepción was lost somewhere in the Mariana Islands on its return voyage. I started my search for it at the British Library, because any big loss at that time would have been of interest to the British. Then I went to Seville, where I spent about six weeks at the Archives of the Indies, combing through administrative records from 1638 to around 1720. There I learned the island where the ship wrecked. Which is more difficult than it may seem, because there are a dozen islands and each one has three different names that sound very much alike. I knew the first Spaniards on the island were Jesuit missionaries, so I arranged to visit the Vatican to look at the records of the Marianas mission. Some were Latin, some were Spanish, some were French, some German. I’m not a great linguist but I’ve learned to read half a dozen languages. Eventually, I came across a note from a missionary who said he was going out to baptize some children. He named the village, adding, “where the galleon was lost.” Now we knew exactly where to look. So, the salvage ship arrived and the first diver went into the water. He came up almost immediately and said, “There’s an old anchor down here.” That was the Concepción.

What’s your latest project?

My current work is on an early packet ship sunk by pirates off South America and another World War II vessel sunk by a U-boat in the Caribbean, which was carrying a cargo of several thousand tons of copper ingots. At current prices this would amount to about $12 million.

Lost + Found

Hebb’s research takes him around the world in search of fabled shipwrecks from the age of sail and beyond. Over the years his work has helped identify scores of sites, including three in the coastal waters of Mozambique that together contained 30 historic wrecks. Here are some highlights:

The Santa Maria De Gracia Y San Juan Batista, aka the Tobermory galleon, sunk off the lsle of Mull, Scotland, in 1588

In an archive housed in a 9th-century citadel in the Spanish town of Simancas, Hebb discovered a first-hand account of the wreck by survivors, some of whom made it back to Spain. From this he determined that while of historic interest, the galleon was not in fact the fabled pay ship of the Spanish Armada.

The Spanish galleon Nuestra Señora de La Concepción, broken on a reef at Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands in 1638

After scouring archives in Mexico, Spain, the Philippines, Italy, England, and the United States, Hebb produced a report so accurate that divers found the Concepción within 15 minutes of entering the water. The first Manila galleon ever recovered, the wreck yielded some 5 million dollars in gold.

The British East Indiaman Princess Louisa, lost near the Cape Verde Islands during a voyage to Bombay in 1743

Hebb homed in on tiny Isla de Maio as a likely site; upon visiting, salvagers located the wreck in a mere 60 feet of crystal water. “I could stick my head in and see the Princess Louisa’s cannon on the seabed,” he says. Among the artifacts salvaged: 20 chests of Spanish silver.

30 individual shipwrecks scattered among three main sites off the coast of Mozambique in the Indian Ocean

Recovered cargo included Chinese Ming Dynasty porcelain from the middle of the 16th century and some 25 pounds of gold that had been smuggled in the ballast of the ship. The porcelain constitutes the most important collection of Ming in Africa.

The SS Gairsoppa, a British steam-powered merchant vessel, torpedoed by a German U-boat 300 miles southwest of Ireland in 1941

Using robotics to work at an astonishing depth of 15,000 feet, Hebb’s clients recovered 60 tons of silver bullion with an estimated value of $210 million.