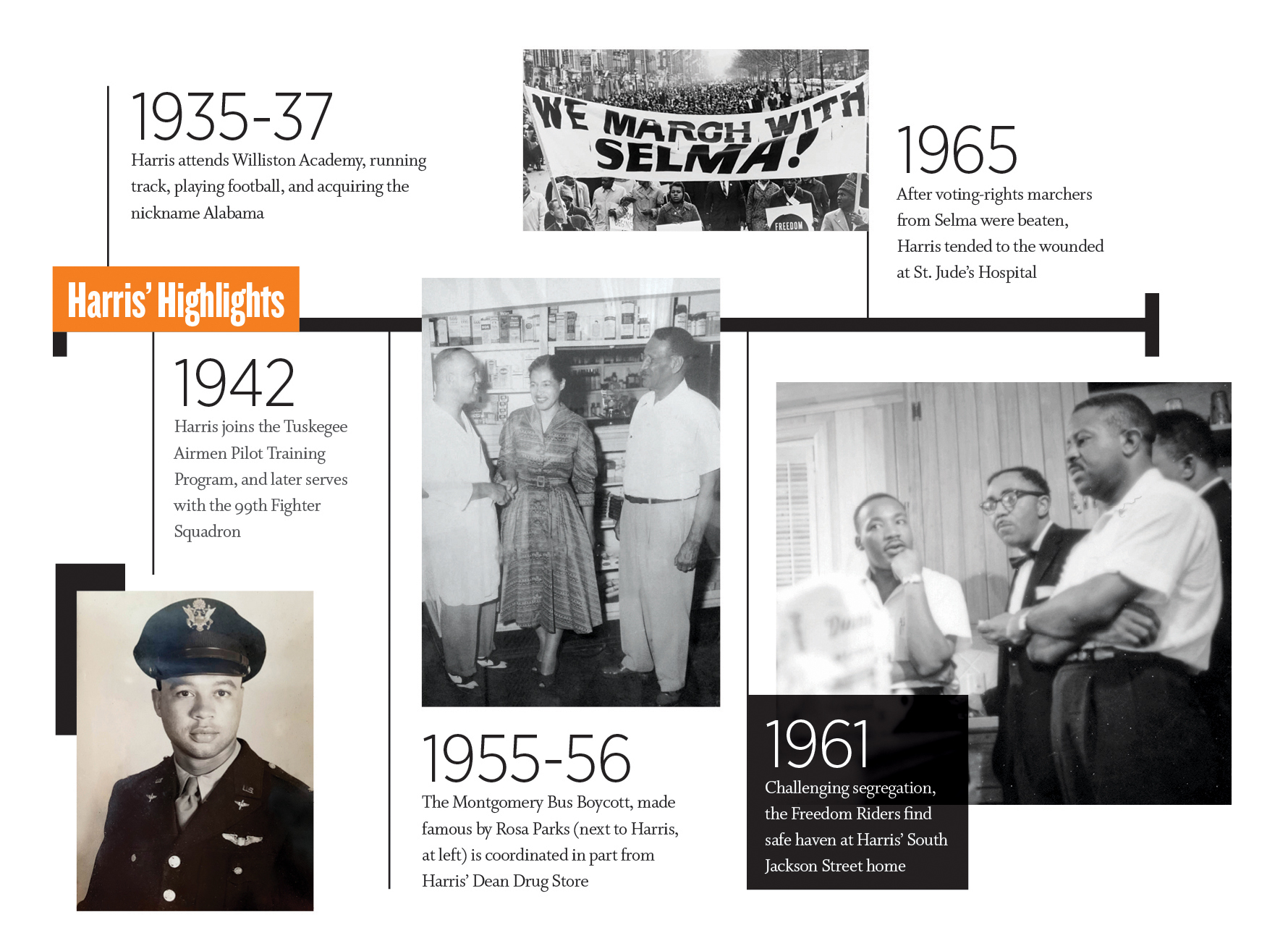

The remarkable life of Tuskegee Airman and activist Richard Harris Jr. ’37

Visitors to Montgomery, Alabama, touring the collection of sites known as the Civil Rights Trail, are sure to stop at the First Baptist Church, where Ralph Abernathy and other activists planned the city’s history-changing bus boycott, as well as Dexter Parsonage, home to a young Martin Luther King Jr. and his family. Just three doors down from the parsonage, at 333 South Jackson Street, sits another historic landmark. The plaque outside announces this as the home of Dr. Richard Harris Jr. (1918-1976), grandson of an Alabama state senator, proprietor of the city’s oldest Black drug store, and a member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen during World War II. But Harris is perhaps most revered for his contributions during three seminal events of the civil rights movement: helping direct the 1955-56 bus boycott from his Dean Drug Store command post, opening this house as a safe haven in 1961 for the segregation-challenging Freedom Riders (including future Congressman John Lewis, who, in a famous photo, sits bandaged in the playroom), and providing medical care to beaten activists at St. Jude’s Hospital after the infamous 1965 voting rights march from Selma.

And yet there is one more facet to this remarkable story: Before Richard Harris became a civil rights icon, he was a student at Williston Academy.

“His father and mother were both very much into education,” explains Harris’s daughter Valda Harris Montgomery, who two years ago, with her sister, opened her family’s house to the public as the Dr. Richard Harris House Museum. Harris’s father—a graduate of Tuskegee and one of the first Black board members of what was then the Tuskegee Institute—“wanted his son to be groomed to go to a Big Ten college,” Montgomery says, but why his parents chose to send him from Alabama to Easthampton in the fall of 1935 remains a mystery. “My sister and I were trying to figure that out. Coming from the Deep South, with all of the struggles and strife that were going on here in the thirties, and yet they send you there? Why there?”

Archival records from Williston Academy note that Harris was enrolled at the school for the 1935-36 and 1936-37 school years, after previously attending the Tuskegee Military Academy for Boys. Though he did not graduate from Williston, students at the time often attended Williston as preparation for college, and the school lists Harris as a member of the class of 1937. He ran track and played football, acquiring the nickname Alabama from his teammates. But aside from a faded clipping from The Willistonian and photos in his yearbook, his family has little other information about his school days. “He never talked about Williston or his days in college or the Tuskegee Airmen,” Montgomery acknowledges. “He was just matter of fact, because that was the way his life was. I don’t think he thought of that as anything special.”

Harris’ academic journey after Williston is considerably less mysterious, as it has become family lore. His parents had been considering sending him to Colby College in Maine, but when he returned home on break from Williston, he met a recruiter who had another suggestion. “He told him, ‘No, you don’t want to go up there. Let me show you where you want to go,’” recalls Montgomery. “And he took him to Fisk University, an HBCU [historically Black college or university], in Nashville, Tennessee. And he fell in love with it.” Harris graduated with a degree in mathematics in 1941, and would later send his daughters to Fisk as well. “He would joke, ‘I’m not paying the application fee for you to go anywhere else,’” recalls Montgomery. A number of the Freedom Riders were also Fisk students, she notes.

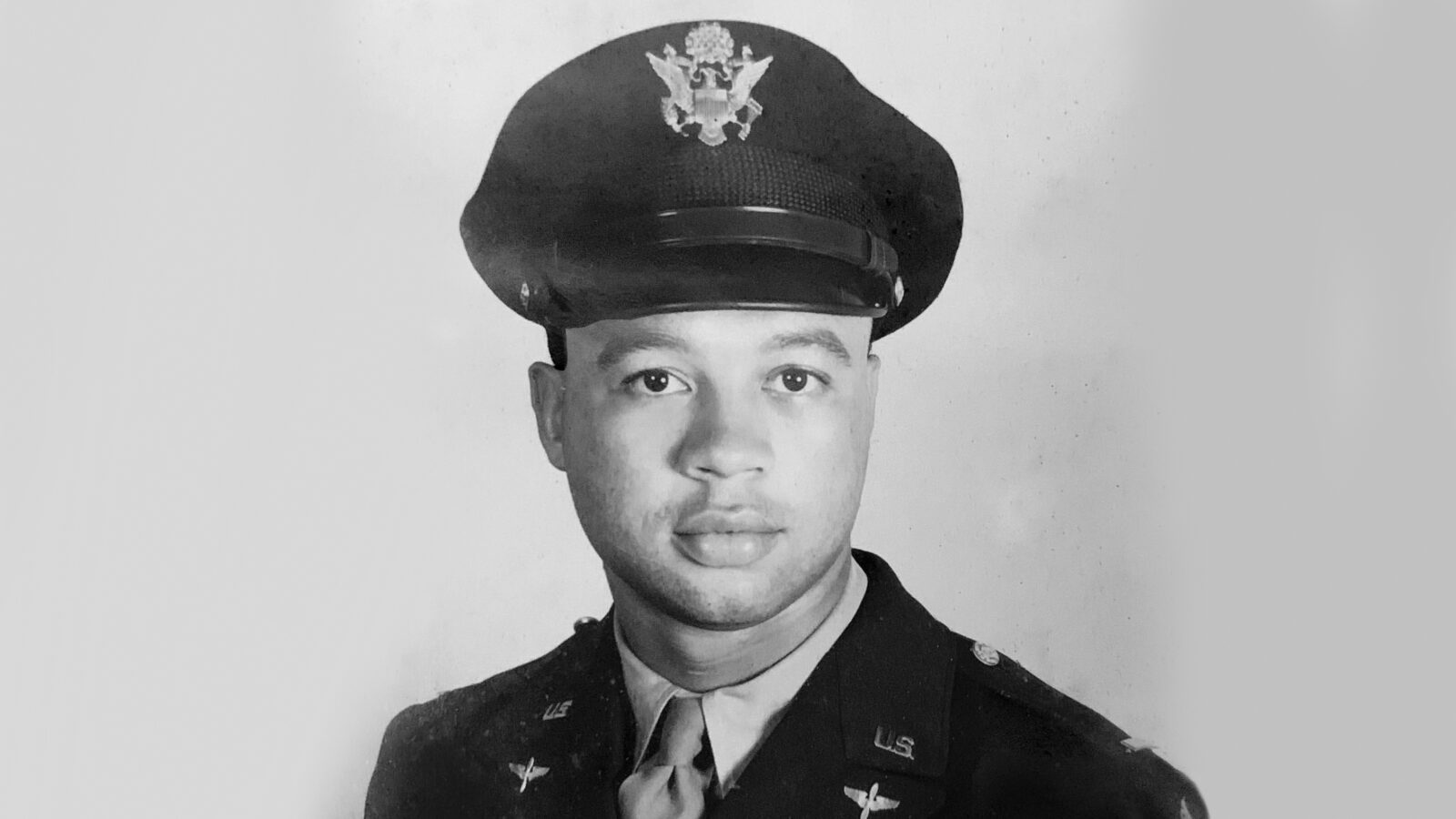

In 1942, amid the outbreak of World War II, Harris entered the Tuskegee Airmen Pilot Training Program and served through 1946 with the 99th Fighter Squadron, the country’s first Black aviators in what was then the racially segregated armed forces. After the war, married to Vera McGill, he returned to Montgomery and began working with his mother at the downtown pharmacy started in 1907 by his father, who had died suddenly at age 54. Observing the importance—and the expense—of the store’s hired pharmacist, Harris returned to school to earn his pharmacy degree in 1953. He eventually took over the store’s operation from his mother and continued to run the business, with his two sons, until his own untimely death in 1976, at age 57.

For his daughter Montgomery, now a retired professor of physical therapy and the author of the Civil Rights-era memoir Just A Neighbor, the process of opening the Dr. Richard Harris House Museum has provided a chance to better understand her father, as well as the pivotal role he played in the history of Montgomery and the broader civil rights movement. What factor Williston played in shaping his development and values may never be known, but, looking back, Montgomery suggests his experience as a young man far from home may have helped prepare him for the many challenges he would face in later life. “When we think about him, with Fisk University and then going into the Tuskegee Airmen, having to go through all of the racial rigors to become a pilot, I think that his exposure with Williston was one that helped him adapt well in any situation,” she says. “Which made it very easy, with civil rights, to just stand ground.”

One thing Montgomery does know is that her father valued education, recognizing it as a means to opportunity. “He was very strong about education,” she says, noting that he sent all of his children to private or parochial schools. “And if anybody needed tuition money for Alabama State, he’d pay their tuition. He was all about moving forward, because he knew education was the key.”