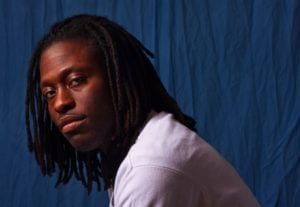

Today’s Dr. Martin Luther King Day Speaker, poet and University of Texas Austin Associate Professor of English Dr. Roger Reeves, posed this question to the Williston community: “Will you open your door for a stranger?” The talk was inspired by King’s final book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community.

During the hour-long Zoom Assembly, Reeves read in full the story of Washington, D.C., resident Rahul Dubey, who sheltered roughly 70 Black Lives Matter protesters in his home when they were being threatened by police. In response, Reeves invited listeners to “make the future” they want to see by “letting in those who are being harmed.”

Reeves, a former Writers’ Workshop presenter, was part of a day-long series of workshops on identity and activism to mark the holiday. He also led an affinity group for Black and Brown students.

Reeves noted that students’ creative output had the potential to have powerful consequences, and offered this example: Ivan Turgenev, a member of the aristocracy in Russia, wrote a book of short stories, A Sportsman’s Sketches, in 1852, outlining the poor treatment of Russian serfs on private estates. The collection is credited with having swayed public opinion in favor of emancipating serfs there in 1861.

“If people need food, feed them,” he said. “If people need housing, find creative ways to house them.” Even creating vegetable gardens in abandoned lots in cities can be a potent form of protest, he said. He cited the Black Panther Party, originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, as an example of a group simply meeting people’s immediate need. The party’s free breakfasts for local residents in Los Angeles inspired the federal Head Start program.

Reeves praised the energy of young people—from the Black Panthers to college students on the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee that organized during the Civil Rights Movement, to young people today working and advocating for social and racial justice. “It’s always been the youth” that’s carried these ideals forward, he said. King himself was only 35 when he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Reeves said that change from the top, from political leaders, is important, and that he didn’t want to let them off the hook. But he argued that citizens also have power to make change. “Sometimes, we need to look at each other,” he said. “We don’t have to have an infantile relationship with the state.”

He talked about how the riots at the Capitol building on January 6 shifted his perspective. He usually runs for exercise every day, he said. But the day after those riots, he stayed home. “I was afraid of what would happen to me.” Reeves is Black, and the people promulgating the “coup,” as he called it, “wanted a future where we didn’t exist.” They were motivated by “immaturity. You have to take an L sometimes”—or a loss in a sports parlance. They were not creating community, Reeves said, but chaos. Revolution, he paraphrased the writer Gabriel Garcia Márquez as saying, brings love, while counterrevolution brings only violence.

However, as dispiriting as the events of January 6, 2021 were, the protests triggered by George Floyd’s killing by police this summer were the largest in this country’s history. They drew more people to the streets than demonstrations during the Civil Rights Movement. “This is a large historical moment,” Reeves said.

In answer to a question about how he fends off hopelessness, Reeves said when he does feel hopeless, he sits with it. Then he asks, “Why, what is making me feel hopeless?” Usually when he does that, he finds that it “feels like a big scary monster, but it’s really more like a cat, or a mouse.” He recommended thinking about hopelessness by making a list. “If you make a list, you’re making it for the future.…If you see a problem, you are the one who can fix it. It may take eight years, it may take 40. This is an ongoing event. This is a marathon, not a sprint.”

Reeves also read several of his poems:

Read more about Williston’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion work. View the entire presentation here.